Corfu, situated in the Ionian Sea, is an island off the North West coast of Greece, approximately 3 hours from London by plane. When I visited the island, it was the end of August and the air was warm and humid. Driving in my pre-arranged hire car from Corfu International Airport, it was less than 10 minutes before I arrived at my destination, Old Fortress. Here I could see restaurants and café bars lining the high streets, and tourists slowly meandering by.

Having been ruled by the Romans, Genoans and Venetians, Corfu’s unique beauty is a reflection of its varied cultural history, apparent upon the style of the city’s buildings and streets. Achilleion Palace for example, was built by Empress Elisabeth of Austria (also fondly known as Sisi), after visiting Corfu in 1888.

I found it interesting to notice how in Corfu, shops close between 2pm and 5pm, only to open again from 6pm until late in the evening. It seems that due to the Mediterranean climate, the citizens of Corfu have adapted their daily lives to avoid the harsh midday sun, and make the most of cooler mornings and evenings.

During my week-long stay in Corfu, I hoped to discover what it was about the family-businesses developed on the island, that made them unique. The conclusion I came to might seem contradictory, yet I believe it accurately portrays what I found there. The citizens of Corfu are both relaxed and committed in the same breath. They are relaxed in the way they do not obsess over business management; rather they prioritise a healthy work-life balance. At the same time, they are committed in their endeavour to provide clients with a first class service or product.

During my week-long stay in Corfu, I hoped to discover what it was about the family-businesses developed on the island, that made them unique. The conclusion I came to might seem contradictory, yet I believe it accurately portrays what I found there. The citizens of Corfu are both relaxed and committed in the same breath. They are relaxed in the way they do not obsess over business management; rather they prioritise a healthy work-life balance. At the same time, they are committed in their endeavour to provide clients with a first class service or product.

During my research, I was particularly struck by an anecdotal story from the community. A bar owner had been facing a rent-increase, demanded by the landlord, which he could not afford. The bar owner had no choice but to move across the road into a new premises. Many of his friends offered—without asking for money in return—their professional skills, such as carpentry and upholstery, in order to help the bar owner reopen again in the new location. As a result, the landlord suffered a huge financial loss, as he was unable to find a new tenant for the vacated premises.

With a community as small as Corfu, it does not come as a surprise to find such a close network of relationships and a strong feeling of camaraderie among the people. Through my interviews with the following three family business leaders, I discovered that success in business isn’t necessarily just about the size of the profit. It is also about how much time and effort you are willing to devote to nurturing a valuable relationship with the community, in order to maintain a quality brand.

Patounis: A 166 Years Old Family Business that Handcrafts and Sells Olive Oil Soap

It was a Monday when I arrived at Apostolos Patounis’s factory. Shortly before midday, he was about ready to start the guided tour full of stories, detailed explanations and demonstrations about his olive oil soap production. The tour is a practical way for Apostolos to cope with the high influx of visitors: “With so many tourists interested in our business, the time available for the actual soap production process was diminishing. I decided a scheduled daily tour starting at 12pm would be the best solution.”

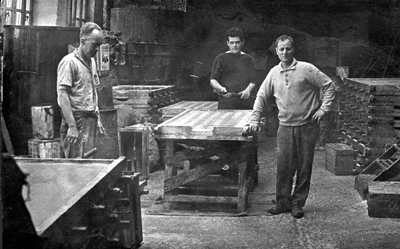

During the tour, I observed as a Spanish boy in my group paused in front of all the rows of soap and looked around curiously; I watched as his gaze fell upon a painting of a man. The painting was a portrait of architect Nicolas Patounis, brother to the 2nd generation family-business leader, Gregory Patounis. It was Nicolas who built the factory in 1891 for the specific purpose of soap production. The Patounis family have preserved many traditional tools and equipment from earlier manufacturing methods. For this reason, the factory was listed in 2008 as a monument of industrial heritage by the Greek Ministry of Culture.

Apostolos’s office occupies one corner of the factory. He grabbed a chair and sat down as he began to tell us about the history of his family business. The wall behind him was covered with pictures of his ancestors, past business members and leaders. I listened over the sound of the electric fan (which was doing little to cool us off). The Apostolos’ family business started 166 years ago…

The Oldest Soap Factory in Greece

It was during the early 19th century when Patounis and Bazakis from Kallarites, a mountain village in Epirus Greece, established the trade of woven capes to the army of Napoleon III. With the trade profits, Patounis and Bazakis bought soap from Marseille, which they then sold in Greece. In this way, the two business partners learned about the soap manufacturing process. In 1850 they founded their first soap production company under the name Bazakis & Co, on the Greek island of Zakynthos. According to available archives, Bazakis & Co is the oldest known soap factory in Greece.

It was during the early 19th century when Patounis and Bazakis from Kallarites, a mountain village in Epirus Greece, established the trade of woven capes to the army of Napoleon III. With the trade profits, Patounis and Bazakis bought soap from Marseille, which they then sold in Greece. In this way, the two business partners learned about the soap manufacturing process. In 1850 they founded their first soap production company under the name Bazakis & Co, on the Greek island of Zakynthos. According to available archives, Bazakis & Co is the oldest known soap factory in Greece.

Their soap soon became renowned across Greece and beyond, with the company experiencing great success. In 1891, business was at its peak; Patounis and Bazakis were able to expand the company by building a second soap factory in Corfu. In the 1930s the two families divided the operation. The Bazakis family stayed in Zakynthos, making soap until the 1970s, while the Patounis family settled in Corfu, where they continue to make traditional soap in the original factory.

The method adopted by the Patounis family to make their soap has been used around the olive producing regions of the Mediterranean for centuries. A soap made of pure virgin olive oil, no additives, and only the essential ingredients for traditional soap, is widely accepted by the region as the most suitable skin cleanser. This recipe is known to clear the skin’s pores by efficiently removing dirt, oily substances and dead skin cells.

Over the last 100 years or so, modern synthetic detergents such as washing powder, shampoo and liquid soap, have become cheaper and easier to manufacture than traditional soap, and have therefore dominated the market. Traditional soap however, seems to be making a recent comeback thanks to the rise of new consumerism, whereby consumers are willing to pay more for ethical and environmentally friendly products.

Apostolos vividly remembers the crisis his industry was faced with back then. He had been working as a mechanical engineer when he took a short break to visit his father. Apostolos was shocked by what he saw; he recounts, “50 years ago there used to be so many soap factories yet since then there has been a massive decline—it seems that nobody wants to be doing it anymore. Even I hadn’t realised how much the industry was, in fact, an important cultural treasure. I told myself, it has taken 140 years of hard work, skill and family tradition to come this far and it is all about to disappear in a day. I can’t let this happen, I must hold on to this.”

His parents had strong objections to his decision to save the industry and wanted him to continue his career path as a mechanical engineer: “My parents never encouraged me to go in this direction because it is a very difficult traditional practice; not at all an easy job. Nonetheless, ever since I was a boy I knew I always wanted to inherit the business. In those days it seemed like a remote dream that would probably never materialise. So that time when I visited my father, I said to myself, this is my last chance and I am going to fight for it. I did encounter some challenges but where there is a will there is a way.”

Guarding Traditional Values

In the 1940s, Spyros Patounis four generations back, studied chemical engineering and established a quality control chemical laboratory for their products. Since then the company has developed a more scientific approach to its traditional methods.

When Apostolos took over the business in the 1990s, his mechanical engineering expertise allowed him to excel: “I designed new cauldrons; no one else could create a cauldron specifically designed for the traditional soap-making process, but I had the right skills to do it. My father, a chemical engineer, was instrumental in establishing the family recipe and passed on a lot of his own knowledge. My wife is also a chemist so her expertise has been extremely helpful too. Both chemical and mechanical engineering as it turns out are integral to the soap-manufacturing sector.”

As in every business, different leaders develop their own unique styles of leadership. Apostolos revealed that while his father was still in charge, he implemented a closed doors policy and many tourists had to be turned away even though they recognised the integrity of the Patounis product.

After taking the helm, Apostolos started granting entry to tourists. While his parents said a brusque ‘Hello’ upon seeing tourists, Apostolos would say a more genial ‘Come on in’, he elaborates: “I learned to speak English but my father never did, so that’s probably one of the main differences between us. By welcoming visitors inside the factory and explaining our traditional methods to them, has inspired interest. In time, word of mouth has spread, travel guides have included us and so naturally more people have come to hear about us. Eventually, it developed into a trend. Many tourists, especially the Japanese, will make a special trip to Corfu just to visit us.” According to Apostolos, Japan is the largest market for Patounis soap.

After taking the helm, Apostolos started granting entry to tourists. While his parents said a brusque ‘Hello’ upon seeing tourists, Apostolos would say a more genial ‘Come on in’, he elaborates: “I learned to speak English but my father never did, so that’s probably one of the main differences between us. By welcoming visitors inside the factory and explaining our traditional methods to them, has inspired interest. In time, word of mouth has spread, travel guides have included us and so naturally more people have come to hear about us. Eventually, it developed into a trend. Many tourists, especially the Japanese, will make a special trip to Corfu just to visit us.” According to Apostolos, Japan is the largest market for Patounis soap.

Having said that, Apostolos is not solely driven by increasing market share. What really matters to him is that his soap maintains a sustainable niche market: “A lot of competing products are in the market just to make profit. Of course I have to look after the balance sheet in order to survive but I am not making big money out of it.”

Initially, the Patounis family began by importing soap from France, however once they had learned about the soap-making process for themselves, they gradually started to cut back on their French imports. One of the major reasons they were able to do this was the advantage of lower local manufacturing costs. Apostolos explains: “The French soaps were of better quality than ours at the start, but now we are exceeding. Nowadays the French use a lot of perfumes and fragrances to make their soaps more attractive, but I would rather stick to the original recipe and not add anything.The authenticity of the product is more important to me than sales.” Several newcomers have attempted to make a mark by recreating the local traditional recipes themselves, but Apostolos appeared not to be too worried about it. He takes great pride in his own products, his family traditions and the stories behind them.

The Patounis family respect traditional values, they have always focused on quality and would never settle for second best. Apostolos remembers the time his father insisted they buy a Leica when shopping for a camera. He would rather go without than buy something of inferior quality. The same mentality applied to his soap. Even when business was declining and all the other soap factories were closing down, his father continued to make soap of nothing less than impeccable quality: “Because he felt that if we were to stop producing our soap, there wouldn’t be any adequate soap left to wash with!”

Apostolos has three children, all of whom are still relatively young. Much to his surprise, his children have shown enthusiasm for making soap just as he did when he was growing up: “Father didn’t want to hand the business over to me because it was going downhill. Unlike him, I hope to pass on the operation fully intact to the next generation.”

Chrisomalis: Grandmotherly Food

“If you’re after wifi and aircon, this place isn’t for you. If you’re after a generous welcome and outstandingly authentic food then look no further. I haven’t tasted moussaka anything like as good as here…”

—A review from Tripadvisor of Chrisomalis, Corfu

Spiros Statiri, owner of bar and restaurant Chrisomalis, served me up a cup of Greek coffee as he invited me to sit down for a chat. After one sip, I immediately experienced the strong, bitter taste. Spiros began the conversation by briefing me on the history of Chrisomalis.

The name Chrisomalis dates back to as early as 1905 when it was run as a beer house, primarily serving beer and a few local dishes. The first owner, back in 1900, bought the establishment from a person named Mamos.

Spiros has done quite a bit of investigative work to uncover the history of Chrisomalis. He remembers seeing an old picture of the restaurant with the sign ‘Mamos’ in a Greek newspaper from 1870. Spiros recalls a conversation he had back in the 1990s, with an elderly local journalist, who had visited Chrisomalis with his great-grandfather as a child. The elderly man claimed the restaurant’s history extended even before Mamos. With this insight, it is not unreasonable to assume that the restaurant is at least 150 years old.

Spiros has done quite a bit of investigative work to uncover the history of Chrisomalis. He remembers seeing an old picture of the restaurant with the sign ‘Mamos’ in a Greek newspaper from 1870. Spiros recalls a conversation he had back in the 1990s, with an elderly local journalist, who had visited Chrisomalis with his great-grandfather as a child. The elderly man claimed the restaurant’s history extended even before Mamos. With this insight, it is not unreasonable to assume that the restaurant is at least 150 years old.

Despite the lack of certainty about exactly when the Chrisomalis legacy was founded, one thing is certain: it has for a long time received a distinguished clientele. The restaurant has been visited and praised by many famous figures throughout the years, popular with the likes of novelist Lawrence Durrell, conservationist Gerald Durrell and two-time Oscar winner Anthony Quinn. The photos of celebrities adorning the walls are a fitting testament to what is so unique about the restaurant.

And, of course, there is the food. At Chrisomalis, food is not just food. Cultural, economic, environmental and sociological factors have all had significant impacts on the local cuisine. Spiros remarked, had you visited Chrisomalis 60 years ago and asked for a “beer”, the bartender wouldn’t be able to sell you one; you would have to ask for “zythos”, the Greek word for beer. This is because the dictatorial government of the mid 20th Century restricted foreign languages and enforced a policy of Greek only.

Spiros’s father, Haralamvos, started working at Chrisomalis as a waiter in 1953 and eventually gained ownership of the establishment in 1972. Although it is now Spiros who is officially in charge, his 82 years old father is still influential in the management of the business. They have both devoted their whole lives to the business.

After Haralamvos took over, Chrisomalis started serving a new style of food. Spiros’s mother added hot food to the menu. As far as Spiros is concerned, it is this “magirio” (which translates literally as ‘cooked food’ in Greek) that represents traditional homeliness. There might have been new and creative culinary ideas developed in other catering businesses, but he wanted his restaurant to stick to the traditional grandmotherly kinds of food that everyone is familiar and happy with. Spiros told me that some customers from England would even visit on the last day of their trip, especially to buy moussaka to bring with them on the plane.

The Greek financial crisis is having a massive impact on his restaurant, Spiros lamented. A bunch of parsley used to cost 50 Greek drachmas but now costs 1 Euro (ca. 330 Greek drachmas). The price has dramatically increased. “It’s a major concern when you have only 20 tables a day to turn over and pay your taxes. I will have to let some of my employees go for these reasons.”

Chrisomalis is more like a friend’s place than a restaurant. Spiros has been there for thirty years living and working with his family, day and night: “There have been many happy moments and of course, some intense ones; but at the end of day, I feel comfortable and satisfied because we are a family.”

“Some people would have thought twice about getting into the family business. If a father has developed a career in law or medicine, he would of course wish for his children to continue his practice because of the prestige and substantial income. In my case, as a restaurateur I’m aware just how much hard work and time the industry requires, and therefore wouldn’t necessarily expect my children to follow my path.”

That said, Spiros immediately stood up with a smile the moment he saw a customer walking into the restaurant.

Corcyra Water Sports: From Passion to Career

Elina Poulimenou has known for a long time that neither she nor her brother Andreas want to take over Corcyra Water Sports, the family business owned by their father, Yannis Poulimenou. Her parents encouraged them to take a different path: go to university, get a degree, and hopefully lead on to a bright and successful future.

Yannis’s Corcyra Water Sports business is located in Gouvia Bay, adjacent to Corcyra Beach Hotel. The luxury hotel is also a family-run business, established in 1963 it benefitted from the Greek tourism boom of the 1980s thanks to the rise of package holidays.

It all started in 1972 when Yannis first started work at Club Med as a water ski coach, before moving to a number of other ski schools. He enjoyed life on the water so much that he decided to make a living from it. He joined a water sports business founded by a friend of his, offering activities such as water-skiing, wake-boarding, paragliding, inflatable rides, pedaloeing and canoeing. In 1980, Yannis took over the business when his friend left to open another ski school in the south of Corfu.

Many young men come to Yannis’s jetty to work during the summer break. Head coach Makis was one of them: “When I first came in 2001 I was just helping out. I wasn’t driving a boat because I didn’t have a license. I was here for a couple of months but not for the whole season because I was still at school. I came back every Summer even after I started university.”

Many young men come to Yannis’s jetty to work during the summer break. Head coach Makis was one of them: “When I first came in 2001 I was just helping out. I wasn’t driving a boat because I didn’t have a license. I was here for a couple of months but not for the whole season because I was still at school. I came back every Summer even after I started university.”

In 2006, Makis finally got his license and was able to drive a boat. Even though he was studying computer science as a university undergraduate, he knew he would never work as a computer scientist and enjoy it nearly as much. So Makis decided to go into water sports. Between May and September every year, he comes here to work full time and is now second-in-command of the business.

After years of working closely under Yannis, Makis has made some observations in regards to the business. For a start, winter is the off-season for businesses such as theirs because many of the shops are closed. The summer season may begin in early May however it remains fairly quiet for the first couple of months. Business tends to pick up during the first week of July as soon as the school holidays commence: only when families with children begin filling the hotels is it time for the real work to start.

In his view, schoolchildren and families are their main target groups. When families leave, business goes down as result. Corcyra Water Sports stays open to the public well into October. Even though they are not in contractual agreement with the hotel during this period, they feel the need to stay open as long as the hotel does because they wouldn’t want guests to complain about the lack of activities available. Makis has regular conversations with the hotel and is fully updated with their schedule, he will finish two days before the hotel closes for the year. As a part in the local tourism supply chain, there is no reason to remain open once the hotel is closed to visitors.

During the off-season, there is still necessary work to be done before they can leave. Maintenance is sometimes needed as the iron and wood jetty can get damaged over the winter. Makis explained that their winter break between November and April is 4 months long. The long winter break may seem like a great perk to outsiders but since they don’t have a shift system, everyone works from 8 a.m. to 9 p.m. everyday, so it is a much needed break.

When considering how the family business model has survived, Makis believes cost is an important factor. Hiring many staff to work for you is a luxury not every business can afford. One way to get around this problem is to keep everyone in the family working together. This way, hiring extra staff is only necessary if another pair of hands is really needed, however Mikas adds that blurring the boundaries between work and home life can be stressful at times. In his opinion, the Greeks are more traditional and more relaxed, but often do not run businesses in a professional way.

Elina and her brother help out at their father’s jetty from time to time. Although she is not working for her father, she believes she can add value to the family business by helping with their marketing and public relations. Elina is currently a management consultant for luxury goods and Andreas is studying Classics. Their mother, Debbie Jones, who used to work alongside their father, is now a private tutor.

Yannis is a quiet man but he works in perfect partnership with Makis. Elina said Makis has been responsible for social media and customer relationship management. Makis’s father passed away a few years ago. His father and Yannis were very good friends. Elina elaborates: “As far as my dad is concerned, Makis is like another son to him. As for passing the family business on to the next generation, blood isn’t so important when it’s still someone you love and trust.”